In what looks like it will be the last in this series, for a while, Brandon Oto of EMS Basics wrote this comment to Rhythm Interpretation and Inattentional Blindness.

Rogue,

We’re talking past each other a bit, and I think we’re in agreement on most points.

Probably, but I think that there are a lot of important points that we are covering that are not well covered in paramedic school or in continuing education classes, such as ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support) or PALS (Pediatric Advanced Life Support).

–

I agree that a rhythm should be fully interpreted in all its particulars, and that our providers should be trained to do this. I agree that shocking sinus tachycardia is not advisable (indeed, I lean towards your camp that shocking anything stable may not be advisable).

What good reason would we ever have to shock sinus tachycardia, when we know that the sinus node is already controlling the rhythm? If we knock the sinus node out, then we have to hope for a junctional rhythm or a ventricular rhythm. these will not be better than a sinus rhythm, even if the sinus rhythm is ridiculously fast.

As for shocking something that is stable, what would be the reason?

ACLS and PALS do not encourage this outside of the hospital.

–

In particular, as you state, “A lack of clear P Wave association would make it much less clear that this would be sinus tachycardia.” That’s the scenario I was imagining, because with many tachycardias, that’s what you’ve got — not clear P waves, as we have here, but a rapid mess.

If there are no visible P Waves, or if the P waves are visible, but dissociated from the QRS complexes, then we should presume that it is not sinus tachycardia, unless there is some other good reason for believing the tachycardia is sinus.

And I know you would agree that, in general, the rate is an important part of any interpretation — otherwise we wouldn’t even be able to call this a “tachycardia”!

Yes, the rate is important, but not for determining if the rhythm is sinus.

The rate is important for helping to determine if the patient is unstable due to the rhythm. An otherwise healthy 20 year old patient with a rate of 220 can be expected to be very symptomatic due to the rate. If the patient is unstable, it may be presumed that the rate is the cause. Still this rate does not tell me anything about whether the rhythm is sinus, junctional, atrial, ventricular, or some combination of these.

Nothing.

Tom Bouthillet posted a comment stating that he likes using the formula 220 – age (in years) for the maximum heart rate to determine if the rhythm is sinus. I disagree, but feel that the formula may be helpful in determining whether an unstable patient is unstable due to the rate.

A 50 year old patient with a heart rate of 152 is below the maximum calculated heart rate. I should work on maximizing oxygenation and intravascular volume, rather than rushing to cardiovert. I should strongly consider other possible causes of the symptoms, rather than focus on the heart rate.

Is someone amped up on Red Bull, or caffeine, or cocaine, or amphetamines, or even repeated injections of epinephrine for refractory asthma going to benefit from cardioversion or for treatment of the cause of the rapid heart rate?

–

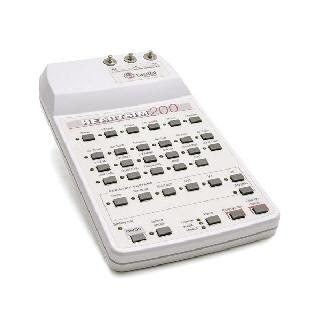

Look at both of these rhythms. Both were labeled as SVT.

Image credit.[1]

–

Image credit.[2]

–

One of them would receive my typical SVT (SupreVentricular Tachycardia) treatment, which begins with a vagal maneuver (slow large bore catheter insertion to provide a route for an adenosine bolus to be slammed in as quickly as possible without blowing the vein. Then there are the other vagal maneuvers available. Some of these may slow the rate to the point where I can see P Waves, or to the point where I can see that there are not P Waves. Another choice is to run the printer at double speed (50 mm/second) or to pull the paper through the printer faster to simulate a faster print speed. These may help to make P Waves visible.

Rather than cardioversion, I will use adenosine for SVT. It works almost as quickly and is much less painful for the awake unstable patient.

–

–

For ventricular rhythms, medication is essentially a waste of time, but all I can do is call command for permission to not give lidocaine or amiodarone.

–

But obviously nobody’s thought processes should *stop* at that point, and there your point is well made and I agree.

On that we completely agree.

–

Thanks for the talk!

It is always a good exercise to debate someone with a different approach to patient care.

Tom Bouthillet and I occasionally debate this kind of stuff, too.

–

Footnotes:

–

[1] Archivo:SVT Lead II.JPG

Wikipedia Spanish

Image

–

[2]Atrioventricular Re-entrant Tachycardia

Thumbnail Guide to Congenital Heart Disease

Article

.

Subscribe to RogueMedic.com